The classic image of the French plague doctor with the beak mask has been circulating on social media. The proboscis, filled with herbs and spices, apparently safeguarded the wearer from poisonous air borne particles or miasma. While there’s little evidence this was ever used, its shadowy theatrical horror still captures the imagination. It reminds us that PPE – personal protective equipment – is not a recent phenomenon.

The classic image of the French plague doctor with the beak mask has been circulating on social media. The proboscis, filled with herbs and spices, apparently safeguarded the wearer from poisonous air borne particles or miasma. While there’s little evidence this was ever used, its shadowy theatrical horror still captures the imagination. It reminds us that PPE – personal protective equipment – is not a recent phenomenon.

Few of us would have given much thought to PPE a few months ago. Now, in the wake of a pandemic, it’s central to global news. We see doctors and nurses wearing a patchwork of coverings (if they’re lucky), hospitals and care homes fighting to procure equipment, small businesses printing face shields and shoppers making and wearing masks.

From the plague mask and today, there is a long and fascinating history of people taking PPE into their own hands. Here at POP we mapping clothing inventions over two centuries. Studying the history of PPE, amongst other things, reveals the many unusual ways people have protected themselves and others from risks and threats. It reveals insights about who and what is considered important and valuable at different times.

From the plague mask to today, there is a long and fascinating history of inventive people taking PPE into their own hands.

Clothing patents are particularly fascinating data as they provide glimpses of life at different times, what worried people and what they did about it. How are different bodies clothed in different discourses at different times? Patents enable us to map inventions against each other, across time, space and social and political happenings to explore where we’ve been and where we might be headed.

While we are only at the start, there are already some striking insights in our research. For one thing, we did not expect to find such an enormous range or volume of PPE from early 1800s – in the form of patents for masks (14,477), gloves (6,225), helmets (1,904) and full protective body suits (890). And, the range of threats and risks are both familiar and growing. We have always sought to protect ourselves and given the current context and climate, this shows no signs of abating. Yet despite this not everyone is protected.

Yet despite this, not everyone is protected.

From fire to shipwrecks and from automobile crashes to biohazards, following are a few examples of the extraordinary range of PPE inventions in the patent archives:

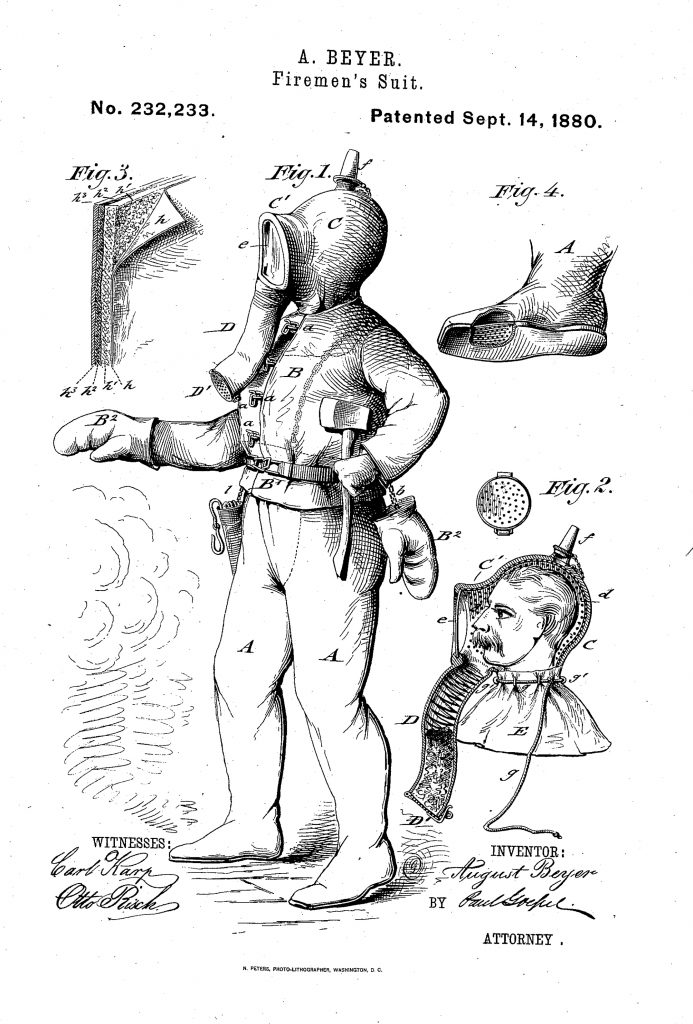

1880 FIREMAN’S SUIT (Pat. US232233A)

August Beyer, an American inventor, designed this full body suit ‘to be able to approach closely to the fire and to pass through without danger of injury’. A jacket, trousers, gloves, shoes, helmet and even suspenders were made of special ‘fire and waterproof material’.

1912 OVERCOAT FOR MOTORISTS (Pat. US1197823A)

Patented by Mathias Stein, a Hungarian inventor, this invention aimed to mitigate the effects of ‘being thrown out of a car and flung with some force against some fixed object or on the roadway’. It apparently doubled as a lifesaving coat for seafarers and aviators.

1916 LIFE SAVING SUIT (Pat. US1197823A)

Shipwrecks were such a common experience that inventors sought to equip passengers with individual devices to assist survival while awaiting rescue. Benjamin, E. Henry, an American inventor, devised a ‘life saving suit’ which ‘when not in use may be packed and carried as other baggage’. What is fascinating in many of the patent illustrations is the context of use in which the invention was imagined. Here, we see the passenger shaking the suit out of the case, climbing into it, fleeing the ship and bobbing comfortable in the water (while eating snacks!).

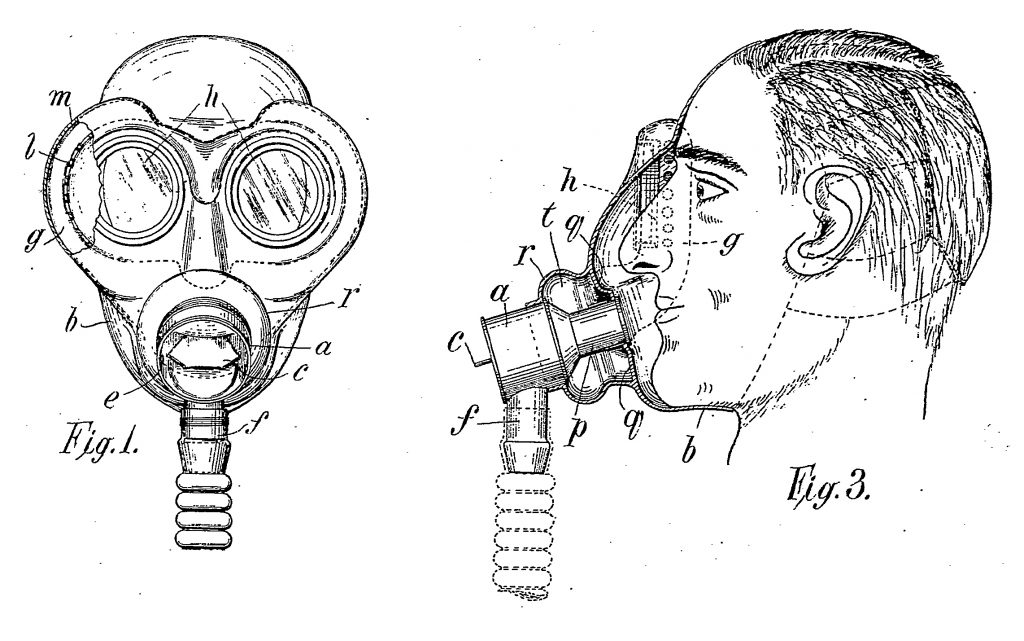

1923 GAS MASK (Pat. GB297890A)

Lots of gas masks were invented for warfare and industrial purposes. This British invention sought to ensure the ‘gas-tightness of the face-piece’ and minimising ‘moisture on the eye-pieces’.

1953 SURGICAL MASK (Pat. CA492369A)

This Canadian operating theatre mask also aimed for a good facial seal. The inventor, Leduc J. Edouard, aimed to ‘prevent exhalation of vapors and germs whilst at the same time permitting easy breathing’.

1986 COLD & WATERPROOF LIFE JACKET (Pat. JPS6124695A)

This Japanese invention combined waterproof clothes with life–saving . The aim was ‘to make it easy to be found by searching from air when a man is drifting about in the sea by expanding a floating mark which is usually attached to the main life jacket in a rolled form’.

Why does this matter?

PPE has radically changed from the 1800s to today. Yet some things are notable over time – namely who is inventing and for whom. As per the nature of legal systems and gendered rights at different times, more men than women have patented ideas and they have generally invented things for people like themselves. (Even in this century, while there is more diversity, there remain many similar male shaped bodies in illustrations and descriptions.)

This is not to say that other people didn’t use these inventions. They probably did. They have to. The point is that they were traditionally rarely the focus of formal inventive attention. This matters because patented inventions tend to rest upon assumptions – height, build, hair, facial features, jobs, physical abilities etc.

Dominant representations of particular types of ‘normal’ reinforce civic roles and responsibilities by equipping certain people to respond to challenging circumstances and ensuring their safety while they do it. Put simply, a particular type of male body is generally better materially protected to be in and to deal with dangerous conditions – and has been for a very long time.

For PPE to work, it has to fit.

For PPE to work, it has to fit. As recent reports and books have argued, much commercial PPE is designed for a universal body – a specifically shaped male one. Women, other marginalised groups and differently sized men tend to be overlooked and under resourced. Female care workers might account for the majority of NHS staff, yet available PPE does not.

Of course, this inventive bias isn’t necessarily conscious or deliberate, but the results are the same. A lack of diversity means we keep perpetuating the same problems. To change this requires different focus from the start – from the point of invention.

At POP we are interested in how inventors create novel forms of clothing that reinforce or alternatively resist, subvert and disrupt social and political norms and beliefs, and in the process, bring new expressions of citizenship into being. In this case, we are seeing increasing reinforcement of particular types of protection for specific bodies – leading us to ask questions like:

How and why do some bodies get more protection than others? Does the abundance of PPE for some and lack for others create different kinds of political subjects? Does this map onto other existing (and stubborn) forms of visibility, invisibility, inequality and injustice? Does this create more-than-citizens and less-than-citizens?

We need inventive ideas more than ever.

Global challenges such as COVID-19 create conditions ripe for invention. Law firms and the International Property Office have reported increased patenting activity in the first half of 2020, compared to past years. While data on the nature and volume of inventions will not be available until next year, it is likely that a majority will come from male inventors.

This reflects other areas of creative endeavours at this time, such as research and writing. Journal editors have noted productivity is up for male authors and down for everyone else. The fact that enforced isolation has enabled and inhibited people along race, class and gendered lines is not news. The risk and opportunity of this lies in what happens next.

We need inventive ideas more than ever. But, unless more inventors think widely for a range of bodies, users and uses, then we will continue to reproduce the inequalities we are dealing with today.

References:

Pat. US232233A. August Beyer, State of New York, USA, ‘Fireman’s Suit’, 14 September 1880. Accessed from the European Patent Office (EPO) Espacenet www.epo.org

Pat. US1197823A. Benjamin. E. Hervey, State of Idaho, USA, ‘Life-Saving Suit’, 12 September, 1916. Accessed from the EPO Espacenet www.epo.org

Pat. GB191221101A. Mathais Stein, Budapest, Hungary, ‘Protective Overcoat for Motorists and Others’, 11 September 1913. Accessed from the EPO Espacenet www.epo.org

Pat. GB297890A. John Ambrose Sadd, Porton, County of Wilts, GB ‘Improvements in or relating to Respirators, Gas-masks and other Life Apparatus’, 21 November, 1923. Accessed from the EPO Espacenet www.epo.org

Pat. CA492369A. Leduc J. Edouard, Canada. ‘Surgical Mask’, 28 April, 1953. Accessed from the EPO Espacenet www.epo.org

Pat. JPS6124695A. Orii Katsuo, Sema Takashi and Yaguchi Mitsuru, Japan, ‘Cold and Waterproof Lifejacket’. 3 Feb 1986, Accessed from the EPO Espacenet www.epo.org

October 13, 2020, 11:01 am

June 30, 2021, 8:36 am

November 5, 2021, 10:33 am

November 5, 2021, 12:21 pm