In this first of a series of blog posts we’re going to share some of our research relating to one Annie Williams.

Annie held multiple patents for a skirt elevator (also known as a skirt lifter) that she invented. Here we trace her journey from Wales to a new life in Canada, speculating on the motivations for the move and for the invention. What role might the skirt elevator have played in enabling Annie to better fulfil her multiple roles as mother, farmer and active member of the local white settler community’s social scene?

Detail from US Patent 1,039, 871 showing the arrangement of cords and plates that enabled the skirt to be lifted.

Born in Wales in May 1870, Annie Moore married Frederick Williams in October 1888. The father of the bride and the father of the groom were both licensed victuallers, giving two pubs in Rhymney, South Wales, as their residences at the time of the marriage. Rhymney had an industrial heritage of iron working and coal mining; a context that was set to erupt in a series of riots and strikes across the valleys in the early 1900s. We can imagine that in the late 1800s life here would have been quite challenging, even for those not working at the furnaces or down the pits. Were poor living conditions and increasing social tensions contributing factors for deciding to build a new life elsewhere?

The 1901 census shows Annie and Fred (now with two children) living on the northern edge of Cardiff. In 1909 the four of them emigrate to Alberta, Canada. By the 1911 Census of Canada, they are established in the nascent settler community of Gleichen as farmers.

From resources such as https://onthisspot.ca/cities/gleichen/gleichen, we begin to better understand the context of the Williamses new location. Gleichen grew up around, and because of, a siding of the Canadian Pacific Railway which was built in 1883. Before the arrival of White missionaries, trappers, ranchers and railway companies, this location had been a key site for camping, hunting and travelling for the Siksika (Blackfoot) First Nations. By the time the Williams family arrived, the Siksika and adjacent groups had had to cede lands within this traditional territory under (still disputed) Treaty 71, and a reserve had been established adjacent to Gleichen. Not yet incorporated with town status, Gleichen’s history was already intricately bound up in processes of colonisation and resource extraction. The restriction and displacement of First Nations people and the expansion of railway infrastructure were both two key mechanisms for achieving this2.

The significant subsidies received by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company for taking on the difficult task of completing the railway connection between Eastern Canada and British Columbia included 25 million acres (100,000 km2) of land, typically situated along the route of the railway. In the area around Gleichen, this was rolling prairie rather than good quality agricultural land. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) marketed and sold plots of this land to immigrants, and we know from an account from Fred Williams Jr.—the son of Annie and Fred Williams Snr.—that his parents bought land here after participating in a tour organised by the CPR. This account can be found in The Gleichen call: a history of Gleichen and surrounding areas, 1877-19683. We wonder what the incentives might have been that motivated the Williams family to relocate to a far-away country only three years older than Annie herself. Did life in Canada turn out as she imagined it would? Did she consider it an improvement on her life in Wales?

In the account referenced above, Fred Jr. recalls some of the challenges involved in starting their new and completely different life in Canada, describing temporary accommodations and then being amongst the first in the community to have hot and cold running water and a septic tank at their newly built farm house. The Williams family were starting from scratch to establish their home and their farm and we wonder to what extent they embraced this challenge and whether the invention of the skirt elevator was another facet of a mindset that relished a practical approach to problem solving.

This photo gives a sense of the landscape of the Williams farm. “Blackfoot people gathering buffalo bones at Fred Williams farm, Gleichen, Alberta.”, 1943, (CU1195303) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

It’s hard to imagine the scale of the terraforming project required to turn what was probably viewed by the settlers as empty wilderness into a viable farming enterprise—there would undoubtedly be a lot of ploughing involved! Fertile conditions for planting the seed for designing a skirt elevator, as the fashion at the time was for long skirts that would have been very prone to getting dirty by coming into contact with the ground and muddy shoes. (I like to think of this as an act of resistance from the soil in response to being torn apart by this sudden influx of new farming practices.)

Here is how Annie summarises the function of her invention in one of the patent documents:

“The invention relates to devices for lifting the skirts of ladies’ dresses for the convenience of the ladies in case they are overtaken by a storm or even when the weather is pleasant overhead but the streets damp or muddy, and the object of the invention is to provide an inexpensive, inconspicuous, easily attached and operated device of this kind which will obviate the burdensome necessity of grasping the skirt by the hand to raise it and the possibility of soiling or creasing the dress while holding it.”

The reference to streets suggests to me a more urban context than working on a farm, was this description indicative of the way Annie herself used the skirt elevator, or a canny way of appealing to a larger, city-dwelling market?

We know from Fred Jr. that his mother often hosted and took part in social events. Perhaps the skirt elevator facilitated an active participation in relational activities that were understood to require a particular style and standard of dress. Ideas and ideals imported over from Europe, now in a context where the pioneer town did not yet have established infrastructures such as paved streets, but where it was vitally important to be integrated into a community of peers.

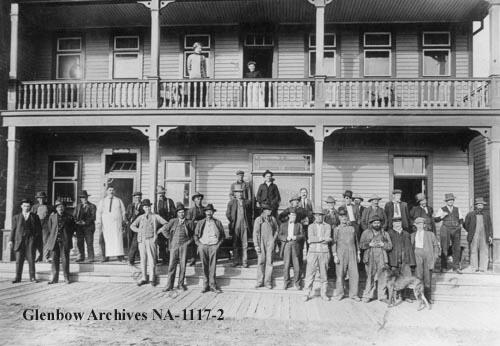

“View of Gleichen Hotel, Gleichen, Alberta.“, 1913, (CU175950) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Above is a photograph of the Gleichen Hotel with its wooden board sidewalk that we understand was made to protect the dresses of the women patrons from the dirt of the street (which remained unpaved until at least the 1970s 4). Mud would have been as much a risk when you were dressed up for a night out and trying to make a good impression on your peers as it was when you were working on the land.

Photographs donated by Fred Jr. to the Glenbow Library and Archives Collection held by the University of Calgary also gave us another important insight into the design function of the skirt elevator. This time the function of obviating the burdensome necessity of grasping the skirt by the hand to raise it. Prairie winds: your hands needed to be free to hold on to your hat!

Detail from “Peter Erasmus, centre, with friends on Blackfoot (Siksika) reserve.”, [ca. 1910-1912], (CU1155324) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

That’s Annie on the right of the group in the image above. We have a few photographs of Annie, but we can’t be sure if we have any visual record of the skirt elevator—it’s possible one or more of the women in the image above are wearing one, but the beauty of the design is that it’s all but invisible, so we’ll never know…

Footnotes

2 See Brody, Hugh. Maps and Dreams. New York: Pantheon, 1981 for more about the project of expansion into the North West of Canada and the CPR’s role in it.